” For two weeks in December, the city of Geneva goes Escalade mad. As Roy Probert found, the people dress up in period costume and pay homage to a humble soup pot that saved the free world. Or something.

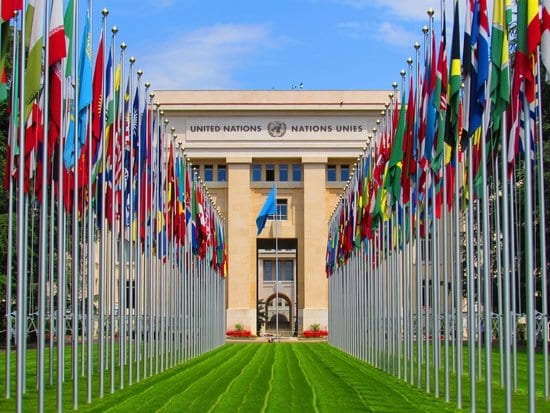

Geneva may be renowned as the world capital of peace and humanitarian work. But during the Escalade period, the citizens of the city show a surprising fondness for guns, swords and canons.

All Swiss people, it seems, have a secret love of dressing up in period costume, polishing muskets and playing fifes and drums. The Genevans are no different. But when they do it, they are remembering a decisive event which arguably made the city what it is today.

The actual day of the Escalade is December 12. It is Geneva’s 4th of July and Bastille Day, though, in keeping with Geneva’s puritan past, it’s celebrated with rather more sobriety. It marks the night when the small Protestant city-state defeated the Catholic forces of the Duke of Savoy and, it’s claimed, cemented its place as a bastion of freedom and tolerance.

“If it had not been for the Escalade, we would probably be French now. And that’s worth celebrating,” says Jean-Michel, who, like his father and grandfather before him, is a member of the 1602 Society, which organises the annual Escalade procession through Geneva’s Old Town.

But what, the visitor will be forgiven for asking, is the significance of the chocolate cauldrons that seem to be in every shop window in the city from the middle of November till the middle of December?

These are “marmites”, and they symbolise the soup pot which played a crucial role in defeating the French hordes.

The story goes something like this: On the night of December 11, the Duke of Savoy launched a surprise attack on the city. As they scaled the city walls with ladders (escalade means to scale) his men were spotted by a woman now affectionately known as Mère Royaume, who poured a pot of boiling vegetable soup over their heads and raised the alarm.

In reality, it was not Catherine Cheynel (Mère Royaume’s real name) who raised the alarm. But she was one of thousands of ordinary Geneva citizens who helped fight off the Savoyards, and her inventive weapon became the symbol of the Escalade.

Today the marmite is made of chocolate and filled with marzipan vegetables. Tradition dictates that the youngest and oldest people smash the chocolate pot and recite the phrase: “Thus perish the enemies of the republic”. In French, of course.

The really serious escalade festivities take place on the weekend closest to December 12. Members of the 1602 Society, dressed in those authentic Reformation period costumes, stage an understated, but fascinating procession through the old town.

At intervals along the way, they stop and a proclamation is read out (the same proclamation that was made after the Duke had been put to flight), muskets and canons are fired and the Geneva anthem Cé qu’è lainô (He who is on High) is sung.

Very few people seem to know what the 68 verses of Cé qu’è lainô mean, as they were written in an ancient Geneva patois. But that does not stop young and old belting it out with gusto. And nowadays they just stick to four verses, which helps.

In short, it’s not particularly complementary about the Savoyards. One verse goes something like this: “On the darkest night they came, and it wasn’t to have a drink. It was to loot our homes and kill us for no good reason.” Thank heavens the Genevans won.

“They have quite a story to tell,” says Keith Kentopp, an American who has lived in Geneva for some 30 years and one of the few foreigners in the 1602 Society.

There are around 2,600 members of the company of whom some 700 are allowed to wear costumes.

“There is nothing Disneyesque or commercialised about this. We know who the main characters of the Escalade were and we all have a role to play,” Kentopp says.

“It’s fun to dress up, but in a time of shifting values, the Escalade represents a kind of continuity. It’s about patriotism, tradition, and basic ideals like freedom.”

It’s also important to place the Escalade in its historical context. It happened at a time of massive religious upheavals in Europe, just before the outbreak of the Thirty Years War.

“It was only a small episode in history. Today we would call it a commando raid,” says Christian Colquhon, a former secretary general of the 1602 Society. “But the following year a peace treaty was signed which brought peace to this region.”

The defeat of the Catholic forces from France and northern Italy also confirmed Geneva’s position as a haven for dissidents and persecuted minorities.

“Many specialists agree,” says Colquhon, “if the Duke of Savoy had taken the city that night, it would not be the city that we know today – city of peace, a city of the world and the headquarters of the United Nations.”